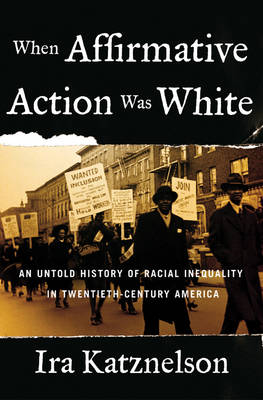

Similarly, Katznelson makes a strong case that the GI Bill, an ostensibly color-blind initiative, unfairly privileged white veterans by turning benefits administration over to local governments, thereby ensuring that Southern blacks would find it nearly impossible to participate. Katznelson supports this startling claim ingeniously, showing, for instance, that while the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act was a great boon for factory workers, it did nothing for maids and agricultural laborers-employment sectors dominated by blacks at the time-at the behest of Southern politicians. And instead of seeing it as a leg up for minorities, Katznelson argues that the prehistory of affirmative action was supported by Southern Democrats who were actually devoted to preserving a strict racial hierarchy, and that the resulting legislation was explicitly designed for the majority: its policies made certain, he argues, that whites received the full benefit of rising prosperity while blacks were deliberately left out.

) finds its origins in the New Deal policies of the 1930s and 1940s. Rather than seeing affirmative action developing out of the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, Katznelson ( Desolation and Enlightenment

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)